The student and soldier have the initiatives

And other dam stories

YICHANG, Hubei — I was not supposed to go to Yichang. I was supposed to go to a small village in Chongqing to stay with my student Ekin and his family. (And the first thing I was going to do was ask him where the hell Ekin came from.) But just two days before I was supposed to leave, Ekin sent the following text message to my phone:

YICHANG, Hubei — I was not supposed to go to Yichang. I was supposed to go to a small village in Chongqing to stay with my student Ekin and his family. (And the first thing I was going to do was ask him where the hell Ekin came from.) But just two days before I was supposed to leave, Ekin sent the following text message to my phone:

Dan,this is ekin. I am sorry that I can not introduce my hometown to you this time,my uncle ask me to beijing for something and i will go the day after tomorrow

So I took out my map, found Fenghuang — my location at the time — and Xi’an — which was supposed to come after Chongqing — and looked at what was in between. I settled on Yichang, which I thought appeared almost equidistant between the two — it is not, I later discovered — and is home to the Three Gorges Dam project, the largest hydroelectric dam in the world and the cause of a great deal of controversy over the past 15 years or so.

This was also an experiment of sorts. I was traveling alone, as usual, and I knew no one in Yichang. How difficult could it be?

The journey got off to a rather inauspicious start — I had no guaranteed seat for the 10-hour train ride from Jishou to Yichang. I had no ticket, either. But I did have Dana, who has a good bit of guanxi. There is a way to purchase tickets on the train. I don’t truly understand it, even now, after having done it once. One of Dana’s travel industry friends — a tight-knit group — helped get me on the train without a ticket. Dana helped me find the part of the train where they sell tickets — a small closet, really — and then once the train started to move and Dana was forced to get off, strangers made sure the process went as planned for me. Later, they made sure I knew to get off at my stop. Sometimes Chinese people really do take pity on the pale faces. (My girlfriend, an American-born Chinese, gets no such sympathy.)

The train was my fifth on the trip to that point. It was also the worst. I was lucky enough to get a sleeper ticket, so I could stretch out a bit, but it was a used sleeper. My seat/bed was covered with long black hair and sunflower seed shells. There was also a dime-sized stain of what could best be described as red goop. Still, I had room to air out my shoes, still soaked from their time spent in a river the day before.

There were six beds in my sleeping compartment, three bunks on either side. The walls between compartments were very thin, and I could feel it every time the passenger adjacent to me rolled over.

The train had no air conditioning. And the man sitting across from me had very bad gas.

But outside my open window, I saw scenes that made me wonder if only four months traveling through China would do the country justice. It was beautiful. People think of China as this big overcrowded country — and it is — but only in the cities. The countryside is wide open and wonderful.

We spent the first few hours traveling through mountaintops, which means tunnel after tunnel — I stopped counting at 23 — and some jaw-dropping views down into valleys. Tunnels, by the way, are also torture for those on the train trying to access the wireless internet on a Pocket PC.

Other than the many text messages I received telling my mobile phone it had entered a new service area, there were few signs that our trip was making progress. Mountains gave way to monotony. There were subtle changes. Where there once were red chili peppers drying in yards, there were now piles of yellow corn.

Homes were always simple shacks. But the outer walls went through an evolution as we traveled further north. Clay bricks turned to wood, then to cinder block, then to whitened concrete, then in Yichang everything was red brick. On the houses, only the tile roofs remained the same.

The areas we traveled through didn’t look so much depressed as unchanged, unaffected by the world’s fastest-growing economy. There were scant hints of what era I was peering into. This was the beginning of a new century … but which one?

Each city we arrived in looked like it was either rebuilding or falling apart. The stops reminded me of Butch and Sundance’s arrival in Bolivia: ominous, empty and a little bit eerie. I wonder if the New York Times traveled through this part of the country before naming this “The Chinese Century.”

Inside the train it was getting hot. Men had taken off their shirts long ago, and were now hiking their slacks above their knees. Some just paraded around in nothing but their underwear. It reminded me of my neighborhood in Shanghai. The flatulent man was now slurping grapes and spitting seeds out the window, or, I should say at the window. A pile was starting to form on the floor. Later, he blew his nose — with no tissue paper — and the results landed right next to the seeds.

There was a teenage boy seated a couple sections over from me. He had been looking my way, off and on, for several hours now. I ignored his stares, as I have ignored thousands of others on this trip. But when the train came to a stop, I saw the boy get up and walk toward me. He sat down on the bed in front of me, held out his hand, and said, “Welcome to China.” I shook his hand, said thank you, and he walked away. He got off at the next stop. It took him eight hours to work up the courage to speak to me.

After about 10 hours, my shoes had finally dried completely. I put them back on as the train approached Yichang. I knew exactly what I needed to do upon arrival: buy my ticket to Xi’an, find a place to stay and spend some time at a local internet bar. No problem.

I don’t remember exactly when the storm hit. It could have been right before I got off the train. It could have been right after. It could have happened at exactly the same time. All I know is that there was a storm — a big, bad one — and I had no choice but to walk right into it. The Yichang train station was one big puddle and my once-wet-once-dry shoes were now soaked again.

There was a man selling umbrellas right beside the train. The one he sold me was perfect — for a 9-year-old girl. It was dainty, powder blue with delicate lavender flowers. I wasn’t in a position to ask for a different one. I was wet.

It was the kind of storm that hits you from all directions and turns umbrellas inside out. I took cover under an awning. My hiding spot turned out to be next to a big wall of windows that looked into one of the station’s large waiting rooms, packed with bored passengers. The tall white guy with wet shoes, an overpacked backpack and a little girl’s umbrella provided some entertainment, however. A crowd formed on the other side of the glass. A little girl, barely past walking age, just stood and pointed. I headed back into the rain, and ran to the ticket office.

I’ve generally been impressed with public transportation in China. What trains and buses lack in cleanliness and comfort, they make up for with abundance. No matter where you are, you can usually find a way to get where you want to go. So I saw no reason why I shouldn’t be able to get a seat or a sleeper for the 13-hour ride to Xi’an that departed two days later. No reason, that is, until the ticket lady told me there were no seats of any kind available on that train. She did this in typical Chinese-ticket-lady fashion: no smile, no eye contact and a tone of voice that made me feel stupid for assuming I could get a seat on a train that didn’t leave for two days.

She said some other stuff to me that I didn’t quite understand. Once the conversation strays from my short script of known words and phrases, I am lost. And Chinese-language-wise, I don’t perform well under pressure. And there was pressure, a long line of people pushing at my back. As usual, some weren’t waiting in line, and I had to elbow them out of the way or pull them away from the window by the collar. No one ever picks a fight with the big white guy.

I walked away from the ticket counter confused. I needed to be in Xi’an by a specific day. I had no idea why I couldn’t get a seat. My shoes made a squishing noise with every step I took. I had a Barbie Doll umbrella. And I was pretty sure I was coming down with a cold.

Meanwhile, a little kid standing next to me shit his pants. I dropped my phone onto the floor. It broke into several pieces. And people laughed at me.

I put the phone back together and got back in line. I had the woman at the counter talk into the phone and explain to my friend Johnson what the situation was. Johnson told me that the station only sells tickets one day in advance, and that if I returned the following day, I should be able to buy my ticket … for a seat or a sleeper.

The explanation satisfied me. I was not looking forward to a 13-hour train ride without a seat. I have watched people travel like that before. They stand in the aisles. They sit on bags. They curl up atop a bed of newspapers on the filthy train floor. At each stop, they watch other passengers like vultures, hoping someone gets off, trying to be the first scavenger to snatch up the unoccupied seat.

I desperately did not want that to be me.

The other items on my checklist for the day actually fell into place quite easily. Two ladies approached me about lodging and walked me to a hotel near the train station. After some negotiating, I had a single room with air-conditioning and a shared bath for RMB 50 ($6) a night. I found an internet place within walking distance and spent the rest of the night there. Walking home, smelling as though I had been to a real bar — everyone is a chain smoker at those places — I walked past a man standing in front of his shop. He was smoking a cigarette, too. And he was wearing nothing but a pair of light blue bikini briefs.

I went back to the train station first thing the next morning, just as I was told to. The sign above my ticket window read: “The student and soldier have the initiatives.” At the time, it seemed a fittingly vague directive. (Later I learned that the Chinese on the sign — xue sheng jun ren you xian — actually makes sense: Students and soldiers get first shot at tickets.) I told the lady behind the glass that I wanted a sleeper ticket to Xi’an, leaving the following day. I even smiled.

“Mei you,” she fired back at me. “There aren’t any.”

She didn’t return the smile.

“How about a soft seat?” I tried.

“Mei you.”

“Any seats?”

“Mei you. Next!”

No seat for you! She was the Ticket Nazi.

I sent a text message to Johnson, explaining the situation. His response? “Sometimes these things happen in China.”

I needed to get to Xi’an. And I needed to arrive on Friday. My girlfriend — who is planning on meeting me about once a month during The Trip — had already purchased her flight ticket to Xi’an. She already booked us a room at the five-star Sheraton there. I wanted to see my girlfriend — and, between you and me, I was also pretty excited about the prospect of a hot shower and a Western toilet.

I caught a bus headed to Three Gorges Dam and thought about my ticket situation during the 40-minute ride.

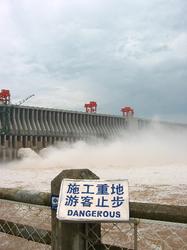

For a variety of rather reasonable — to me, at least — reasons, many people throughout the world aren’t happy about this dam, which will submerge a portion of a very famous section of the Yangtze River and displace approximately 2 million people. The myriad problems with the project have been written about at length (go here for a good summary), and I don’t feel like getting into them here. Only the Chinese state-run media — surprise, surprise — has stories that put a positive spin on the dam, slated to be completed in 2009 (here are some examples of the propaganda).

Speaking of propaganda, there was plenty on the tour bus that took me and four Chinese tourists to the dam after we paid the RMB 65 (!) admission fee. I was expecting something different. Lonely Planet talks of having to hop on the back of someone’s motorcycle to see the dam project. I thought it would be somewhat remote. I wasn’t remotely close. LP’s description is out of date. The whole dam area is sanitized for our consumption. Pay your $8, and you are trucked around to a few dam lookouts. And then it’s time to leave.

“Sail from the great Three Gorges and make China powerful and prosperous!” sang one of the several dam songs on the bus VCD. “Never let our precious river flow away!” ordered another — oddly echoing the feelings of the dam’s many environmental opponents. The songs were followed by an informational video on the whole dam process. It included many slow-motion shots of big rocks tumbling into the Yangtze and the kind of dramatic music you would expect from an awards show. The video featured clips of famous diplomats smiling at the dam construction site. I think I remember seeing Henry Kissinger.

The dam has a cartoon mascot, a little smiley guy in a hard hat, and his image is everywhere. Our guide had him embroidered on the breast of her bright orange polo shirt.

I’m not sure exactly what I was expecting from this dam, but I must say that I was not impressed. This is supposed to be the largest hydroelectric dam in the world — one of many largest-in-the-world items China currently has under construction. There’s the world’s tallest building under way in Shanghai’s Pudong area; the world’s largest suspension bridge, also planned in Shanghai; and the world’s largest Ferris wheel in Beijing. Can we infer from all of these big badges of honor that China also has the world’s largest inferiority complex?

Oddly, from every angle, the Three Gorges Dam just didn’t seem that big to me. Perhaps this was because of the gray day or the fact that it is still unfinished. Or perhaps I just don’t know a big dam when I see one. I suppose part of me was expecting a sheer, clifflike wall of concrete spanning the gap between two imposing mountain peaks. And maybe part of me was expecting to see Harrison Ford do a swan dive into the rumbling whitewater hundreds and hundreds and hundreds of feet below. What I saw looked more like a long, boring bridge.

The dam didn’t really help take my mind off my ticket troubles, and when my dam tour was finished I headed straight to the Yichang branch of the China International Travel Service (CITS). It’s been my experience that anything is possible in China … as long as you go through the proper channels. And sure enough, it didn’t take me long to have an acceptable plan in place. I had a sleeper ticket in hand from Wuhan to Xi’an. And buses for the five-hour ride to Wuhan left Yichang roughly every 30 minutes. It was going to be more than 20 hours of traveling … but I knew I could spend those 20 hours on either my butt or my back. I was satisfied.

I had a celebratory meal of jiaozi at a streetside place near the CITS office. I sat with two older men who wanted to talk, and for a while there, it felt as though we were actually understanding each other. The young female owner of the restaurant approached me with a pen and a pad of paper. She asked me to write my name down — I was the first foreign customer she had ever had.

I took a photo of the friendly folks at the restaurant, and went to bed that night thinking that traveling alone in China wasn’t all that bad.

Click here for photos.

9 Comments

Glad to hear that you’re still alive and getting along fairly well. Following along in your journey. Sounds amazing. Talk to you later. Note new e-mail address.

It‘s the first time i leave comment on ur new website Dan~.Seems everything goes and I’m it will work out soon,hehe.Is it hot there?But in Shanghai now,it’s hot,hehe,though the typhoon just hit here.Hope to know more about ur travel.

Cheers

Longtime fan first time caller…

I must ask do you find the time to travel and write? How much material do you not submit on the website? Can you include more details in the descriptions-though I found the segment on the train ride to be fine.

Thanks, peter

Funny picture :-)

I wish I was in Yichange and guide you :-), have fun!

Dan! Update, Dan! Why you no update? Update! Dan!

For what it’s worth, Chinese people get the exact same stoic treatment from the ticket ladies. When they find out there are no tickets left, the ticket buyers then say something like “zenme ban ne?” and the ticket lady just frowns past them at the next person in line.

I find it very amusing, but probably would less so if it happened to me. Smart man, going to CITS in a pinch.

Don’t know that it’s still so difficult to get a ticket these days. I have been out of the country for too long; but I heard that the ticket is easier to buy and the ladies are more friendly. Guess I am wrong again. After being spoiled in the States for so long, I guess I will storm the ticket office and tear everything down if they tell me “mei yo”. It further dampened my ethusiam to go back to China. Same O same O.

Dan, you talked about reverse shock you didn’t feel when you came back to the States. My theory is that only people like me can experience the reverse shock because if I go back to China from the US, it’s going from a much more developed country to a less developed country. I remembered I felt awkward with the squat toilet in the Japanese airport, because I hadn’t seen one for ten years living here in the States. But I still love going back China to visit, knowing that I still have a permanent home in the US. Whenever I encountered problems and unplesant things in China, I would console myself with the fact that it was just a visit and I would soon be back to the States. But still I feel that China is my home. It’s painfully contradictory. I have asked myself what if US and China were at war with each other. I know I would rather stand in between and be hit by the crossfire than fight for any one of them.

Sorry, forgot to include my email address for the last post.

dan, this is the website of Baoji Tax bureau, but you might love it …

http://www.bjds.gov.cn/bjds/internet/jtds/html/xiuxianyule/kxyk.htm

i happen to find it when i look for a pic for my post, the funny thing is not those pics but who put them into their website